Brands have a tendency to stick to a central European distribution model for far too long. But that central inventory strategy and subsequent stretched distribution lines to the ends of Europe could haunt the brands if consumer convenience continues to evolve towards same-day and micro-fulfilment. The strategic distribution of products over a network of local stock locations in Europe becomes an important weapon for brands to build a direct relationship with the end customer.

If “Direct to Consumer” is the name, then “Distributed Inventory” is the game.

Nineties

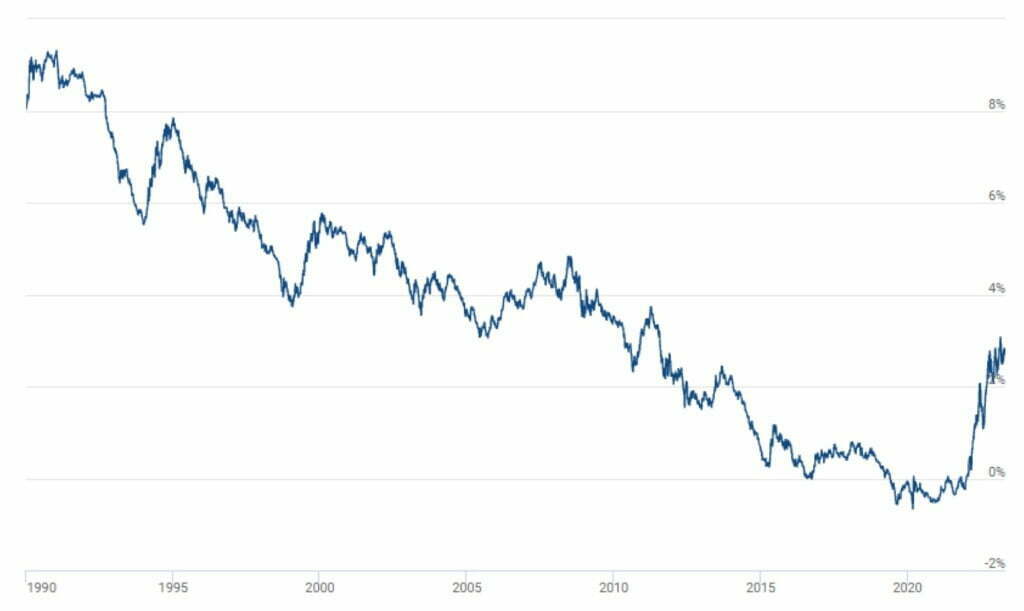

During the nineties Europe became a level playing field for trade with the removal of the internal borders and the improvements of the European infrastructure. Brands could now replenish their customer’s warehouses (wholesalers, distributors, retailers) from one central European location within a few days. Okay, maybe it was still convenient to hold onto a local sales office to keep in touch with the customer, but with a capital market interest rate of 6 to 8% in those years it would be insane to store local stock in every country. European Distribution Centers (EDC’s) emerged everywhere and The Netherlands was successful to attract a large portion of these EDCs.

Figure 1: Capital market interest rate development 1990-2022 (source: Homefinance)

But now the world has changed. National debates on the negative impact of large scale logistics real estate on the landscape is shifting public opinion away from these space-consuming behemoths with their monotonous architecture.

Shape and contents

And not only the shape but also the content of European Distribution Centers (EDCs) requires a reset of a Brand’s mindset: Is centralized stock still the way forward? A few considerations for brands with European ambitions:

1. Direct-to-Consumer

With the rise of E-commerce, more and more traditional brands are looking for a direct relationship with the end customer and are thus skipping Wholesale and Retail. This Direct-to-Consumer movement creates a need to keep stock closer to the customer and to be able to deliver within 24 hours. That is not possible from 1 EDC;

2. Wholesalers become marketplaces

Wholesalers also see their role changing and introduce Marketplaces where they no longer store all products themselves, but have them delivered directly to the end customer using a drop-ship model, and – you guessed it – within 24 hours. An example of “Wholesaler-Turned-Marketplace” is Conrad Electronics;

3. Free money

The steady drop in interest rates since the 1990s gave us virtually “Free Money”, making inventory easy to finance. Yet free money has not led to an increase in inventory in the consumer goods supply chain. Logical, because in the end you have to be able to sell your products instead of stocking it, and every square inch of storage space also costs money. But hold that thought of cheap stock for a second;

4. Network optimization

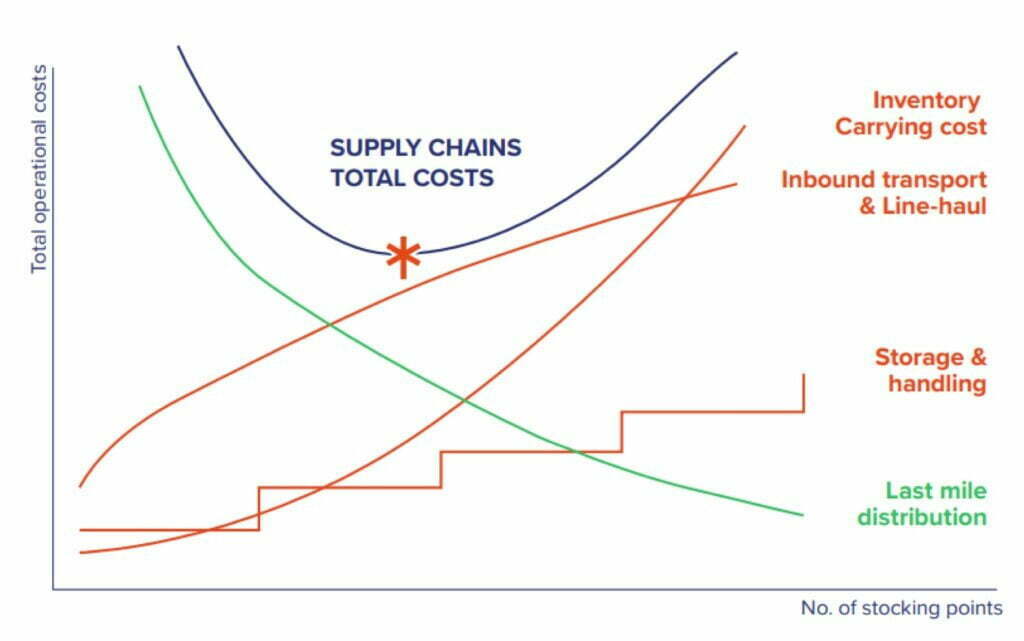

In inventory network optimization models, 4 costs play an important role:

- Inventory Carrying cost: say the costs of financing, management and depreciation of inventory;

- Warehousing cost: the costs for storage and handling of outgoing orders and returns;

- Replenishment cost: the costs of re-filling the stock locations;

- Distribution cost: the costs of delivering the orders to the end customer.

According to the square root of inventory theory, as the number of stock points in a network increases, the first three cost components also increase, but distribution costs decrease. This creates an optimal number of stock locations in a geographical area (for example Europe), for each product category.

Figure 2: Optimal number of stock locations (source: Groenewout/Guru/Supplime)

For the longest time, the sum of these costs leaned towards as few stock points as possible; after all, high inventory costs and low distribution costs favored centralization. But now that fuel prices and driver costs have risen sharply due to scarcity and the carrying cost is still relatively low, the model is starting to shift in favor of decentralization. Especially now that the service argument of same-day and next-day delivery is becoming more important in the customer’s “cost-convenience” trade-off, keeping multiple stock locations is not only cost-effective, but also stimulates revenue;

5. Re-shoring

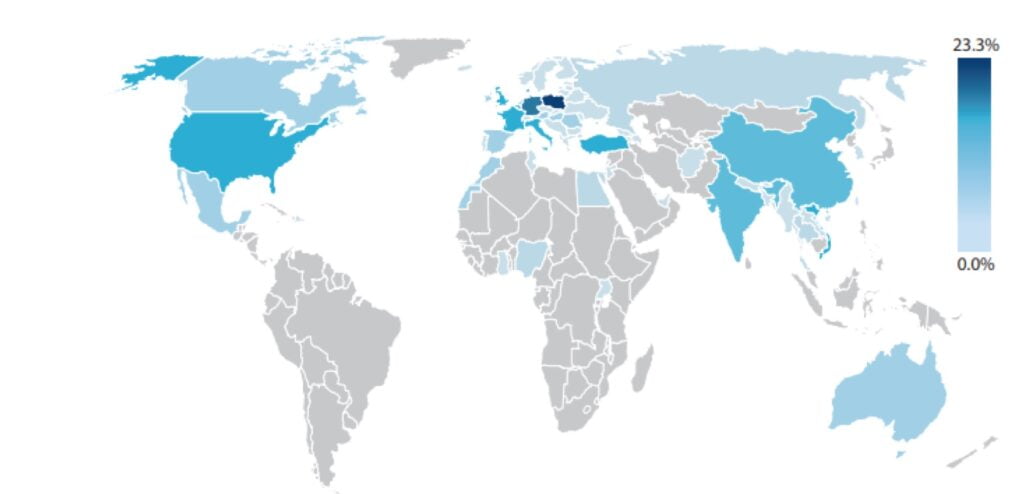

With the recent disruptions in the supply of products from Asia during Covid and the geopolitical developments in China and Ukraine, European companies are looking for ways to minimize the risks of disruptions in their supply chains and make the supply chains themselves more sustainable. A much-discussed strategy here is “Re-shoring”: bringing production back from Asia to one’s own continent. A 2022 study by BCI Global and Supply Chain Media shows that 60% of European and American companies are considering returning part of their production to their own region, with Eastern Europe being particularly popular. According to a Maersk/Reuters report, even 25% of European companies are thinking about sourcing products within the same country where consumption takes place.

Figure 3: Popular re-shoring locations for European companies (Source: Maersk/Reuters Events, 2022)

And with that, several legs under the central dining table of the EDCs are chopped-off. After all, if production becomes regional, carrying costs are low, the classic wholesale and even retail function disappears, transport becomes more expensive and delivery has to be fast, then an era is dawning in which inventory will once again be located close to the customer: decentralization. “Distributed inventory” models are being introduced, whereby brands can serve various sales channels from 1 stock location per country: retailers, marketplaces and Direct-to-Consumer, and replenished directly from suppliers in Europe within 24 hours. And even with interest rates rising, the benefits of a flexible fulfillment network and inventory close to the customer outweigh rising inventory costs, provided the right products and reliable supply can keep local safety stocks in check.

And yet brands with a Direct-to-Consumer strategy are not yet queuing up to cross borders with their own stock, although that is often better for their customer satisfaction and profitability. Why is that?

Fear of the unknown

Keeping local stock means, among other things, looking for a suitable location or fulfillment partner, for 1 or more local carriers, setting up local (VAT) accounting, determining the strategy for stock replenishment and setting up a local return policy. Adapting a webshop to the local language and culture of Slovakia is one thing, but finding a suitable fulfillment partner near Bratislava is a whole different ballgame. I recently heard someone say, “Outsourcing logistics is like dating”.

The knowledge and experience of logistics outsourcing is often not available in-house at the brands, which creates anxiety: companies stick to their central inventory strategy for a long time, sometimes too long, when they enter Europe. This leads to an unnecessary increase in operational costs. For example, I recently spoke to a logistics manager of an online wholesaler in Germany going D2C. A DIY customer from Spain had bought a large powertool on their webshop. They found out the transport costs alone had swallowed up the entire margin of the order (and more). It was clearly time to adjust the inventory strategy.

The easiest method is to outsource the problem to the marketplaces such as Amazon. They offer to distribute your stock within their own network of fulfillment centers in Europe and redistribute it if necessary. At a considerable service cost, that is. Another major disadvantage of the “outsourcing-of-the-problem” strategy is the dependence on 1 sales channel (marketplaces) for allocating all local stock, while servicing various sales channels with the same inventory was precisely the reason to have your own presence in all these countries.

So many brands continue to supply their European customers from 1 central stock, out of the big “Fear For The Unknown”. But this anxiety could well take on an extra dimension.

Micro fulfillment

I have been curious for some time about the Dutch fascination with the “last mile”. In no other European country so many startups are launched per square mile to get products to the customer: bicycle couriers, flash delivery services, electric cargo bikes, local delivery services, same-day delivery, trunking; all hoping for “scalability”, the treasure hidden behind each of the business models. But it does indicate that businesses are looking for ways to make the delivery experience as easy, fast and environmentally friendly as possible.

While the “last-mile” initiatives still mainly focus on the delivery of products that have already been ordered, another phenomenon is now also gaining ground: Micro Fulfillment Center (MFC).

This is a mini-automated warehouse at the edge of town where consumers and professionals can pick up an ordered product or even buy a product without the involvement of a shop assistant or warehouse employee. It is the latest Swisslog invention, the company that turned the mechanization of distribution centers upside down 10 years ago with the introduction of Autostore. Because in addition to the well-known “cube” where moving robots “dig out” bins, Swisslog is also a supplier of mini-load systems for the storage and dispensing of medicines at pharmacies. A logical intermediate form are the fully autonomous mini warehouses that can be placed at strategic locations in urban areas, equipped with a smart range of products. And Swisslog is not alone. Recently newcomer Intellistore and others are offering modular automated storage systems. This creates a new type of stock location as a mix of fulfillment centers and retail stock that needs to be replenished not once but 6 times a day, and that at perhaps 5 or 10 locations per city or urban area.

Figure 4: Micro fulfillment center (Source: Swisslog)

If this form of ultra-fast product availability catches on, brands will have to determine whether they want to join the ride and be present in these MFCs with a specific part of their assortment (and how they want to organize the replenishment of this stock), or whether they prefer to leave last-mile distribution to specialized (whether or not online) retailers.

Whatever the answer to that question, one thing is clear: as a brand, you don’t want to deliver an online order of your exclusive set of kitchen-knives, produced exclusively for you by a factory in Poland, within a few hours to a Chef in Milan from an EDC in Hamburg, do you?

Bart de Rijke is CEO of Supplime BV, a start-up European fulfillment and logistics platform for cross-border e-commerce entrepreneurs and co-founder of The Future of Commerce.

Sources

- Capital market interest rate development: https://www.homefinance.nl/marktrentes-economie/capital market interest/

- Square root law of inventory: https://acumenfl.com/blog/making-sense-of-the-square-root-law-of-inventory-management/

- Reshoring BCI/SCMedia: https://bciglobal.com/en/strong-rise-predicted-in-reshoring-of-critical-parts-and-final-assembly-to-europe-and-us

- Re-shoring Maersk/Reuters Events: https://1.reutersevents.com/LP=33709

- Network Optimization: https://www.groenwout.com/logistic_tool/cast/

- Chief Government Architects about dosing: https://www.collegevanrijksadviseurs.nl/adviezen-publicaties/publicatie/2019/10/29/xxl-verdozing

- Micro fulfillment centers: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Smx_GQezVwY en https://www.swisslog.com/nl-nl/business-solutions/micro-fulfillment-center